Alaska Diary: Day 5, September 4, 2001

We had gotten out first taste of the river. We had encountered only minor difficulties as we floated 17 miles and dropped about 375 feet (about 22'/mile). The river had passed through a flat valley with the major hills well back from its banks. Today the hills (small mountains) came right to the riverbank and both Papa Bear and The Alaska River Guide warned of several sets of rapids. First on the list was a 20-mile stretch of "swift flow through rock gardens" which required "quick maneuvering". Seven miles into this stretch was Upper Falls (aerial photo in Day 1) which required portaging.

We had gotten out first taste of the river. We had encountered only minor difficulties as we floated 17 miles and dropped about 375 feet (about 22'/mile). The river had passed through a flat valley with the major hills well back from its banks. Today the hills (small mountains) came right to the riverbank and both Papa Bear and The Alaska River Guide warned of several sets of rapids. First on the list was a 20-mile stretch of "swift flow through rock gardens" which required "quick maneuvering". Seven miles into this stretch was Upper Falls (aerial photo in Day 1) which required portaging.

We made unhurried departure from Camp 1, as we imaginatively named it. Auspiciously as we left, the clouds began to break up and the sun eventually appeared. It was the best weather since our drop-off day. After a while we realized that the height of the river submerged the rock gardens. We easily floated over them and leisurely watched the tundra-covered hills for caribou (rack gardens) and the partly sunny sky for bald and golden eagles.

We made unhurried departure from Camp 1, as we imaginatively named it. Auspiciously as we left, the clouds began to break up and the sun eventually appeared. It was the best weather since our drop-off day. After a while we realized that the height of the river submerged the rock gardens. We easily floated over them and leisurely watched the tundra-covered hills for caribou (rack gardens) and the partly sunny sky for bald and golden eagles.

The lack of rock gardens confused us. But a GPS reading and map consultation oriented us. Soon we heard the sound of falling water announced that Upper Falls was just around the bend; just where we thought. We quickly pulled onto the right bank, remembering the Kisaralik River Rule: "keep right." Papa Bear's aerial photo showed a portage trail up and over a hill on the left. But he had pointed out a shorter and more direct trail on the right. We checked out the path and carried our gear over the rocks. For an aerial view click here.

The lack of rock gardens confused us. But a GPS reading and map consultation oriented us. Soon we heard the sound of falling water announced that Upper Falls was just around the bend; just where we thought. We quickly pulled onto the right bank, remembering the Kisaralik River Rule: "keep right." Papa Bear's aerial photo showed a portage trail up and over a hill on the left. But he had pointed out a shorter and more direct trail on the right. We checked out the path and carried our gear over the rocks. For an aerial view click here.

A lively discussion began about whether to line the raft through the first Class III rapid. I argued for lining. I pointed out its ease and speed. Norm, liberal in some things and conservative in others, argued for portaging the heavy and bulky raft over sharp and slippery rocks with no regard for our bodies. I eventually and miraculously convinced the lawyer. I held the rope and Norm launched the raft into the current. It hung up on a small rock momentarily and then bobbed through the rapid in a second. The next rapid, 50 yards downstream, was Class IV and there was no discussion of how to proceed. We dragged and lifted the raft over some rocks and flipped it into the pool below. It stayed put because we had tied a rope to a tree near the pool before the final push.

A lively discussion began about whether to line the raft through the first Class III rapid. I argued for lining. I pointed out its ease and speed. Norm, liberal in some things and conservative in others, argued for portaging the heavy and bulky raft over sharp and slippery rocks with no regard for our bodies. I eventually and miraculously convinced the lawyer. I held the rope and Norm launched the raft into the current. It hung up on a small rock momentarily and then bobbed through the rapid in a second. The next rapid, 50 yards downstream, was Class IV and there was no discussion of how to proceed. We dragged and lifted the raft over some rocks and flipped it into the pool below. It stayed put because we had tied a rope to a tree near the pool before the final push.

The pool was filled with silver salmon, the last run of the year. They were close to three feet long and were a deep red color. Hundreds circled in the eddies. At times they seemed to receive a mysterious and secret signal and started to leap up into the falls. But the water was too high and powerful and we didn't see any make it. Only the strongest will make it to the prime breeding streams above the falls.

The pool was filled with silver salmon, the last run of the year. They were close to three feet long and were a deep red color. Hundreds circled in the eddies. At times they seemed to receive a mysterious and secret signal and started to leap up into the falls. But the water was too high and powerful and we didn't see any make it. Only the strongest will make it to the prime breeding streams above the falls.

During the portaging of gear, four caribou spanning three or four generations appeared about 20 yards upstream of us. They ignored us and seemed intent on crossing the river. One started to cross and started swimming madly and got in the current. And we said, "It's not going to make it. It's not going to make it." But it did get across into a lower pool and with a lot of struggling came out on the other side. And then a little one, a real small one did the same thing, and he went even further down but was able to get across.

During the portaging of gear, four caribou spanning three or four generations appeared about 20 yards upstream of us. They ignored us and seemed intent on crossing the river. One started to cross and started swimming madly and got in the current. And we said, "It's not going to make it. It's not going to make it." But it did get across into a lower pool and with a lot of struggling came out on the other side. And then a little one, a real small one did the same thing, and he went even further down but was able to get across.

Then a third one tried it and somehow didn't have the power to do it, and he was swept through the main, Class IV rapid, down into the pool. It went underwater, but emerged pawing the surface and came out on the opposite bank, shook itself off like a dog, and then found a way to climb up a real steep bank to the other side. And then as he as going up I noticed that his right rear knee joint was really swollen. So he had some weakness and that's what prevented him from swimming as strongly as the other ones. And there was a fourth caribou with a pretty big rack, but when I moved to watch the third caribou go down the main falls, he spooked and went up the other side. So that herd was split up.

This whole operation of portaging, lining and watching the caribou and salmon took two hours. We moved on because the large quantity of salmon seemed like a bear magnet to us. Soon we had moved into new geology. We left the ancient glacial outwash of sand and gravel and moved through hills where slate layers had been exposed by the river leaving a very steep and high bank. On one of these hills we saw a group of eleven Yup'ik picking blueberries. All had five-gallon buckets and some had rifles and binoculars. Their v-hulled open aluminum water-jet boats were tied up below them. Outboard motors that sucked in water and then forced out the back allowed them to travel up the shallow river. We learned later that the blueberries are made into "Eskimo Ice Cream, " traditionally seal fat and blueberries but these days Crisco and sugar are added.

This whole operation of portaging, lining and watching the caribou and salmon took two hours. We moved on because the large quantity of salmon seemed like a bear magnet to us. Soon we had moved into new geology. We left the ancient glacial outwash of sand and gravel and moved through hills where slate layers had been exposed by the river leaving a very steep and high bank. On one of these hills we saw a group of eleven Yup'ik picking blueberries. All had five-gallon buckets and some had rifles and binoculars. Their v-hulled open aluminum water-jet boats were tied up below them. Outboard motors that sucked in water and then forced out the back allowed them to travel up the shallow river. We learned later that the blueberries are made into "Eskimo Ice Cream, " traditionally seal fat and blueberries but these days Crisco and sugar are added.

Twelve miles below Upper Falls we came to the confluence of the Kisaralik River and Quicksilver Creek. We checked out a campsite a little way up Quicksilver but chose a gravel bar just below the confluence because it seemed more sheltered from the current wind. We set up camp with the raft acting as a windbreak. We ate and then headed for the tent when it began to drizzle. Norm had appropriated a plastic camo rain jacket that was hanging on a bush near the raft. As darkness closed in, we heard the sound of motorboats coming down the river. One boat stopped and a young Yup'ik got out. Norm stuck his head out of the tent.

Twelve miles below Upper Falls we came to the confluence of the Kisaralik River and Quicksilver Creek. We checked out a campsite a little way up Quicksilver but chose a gravel bar just below the confluence because it seemed more sheltered from the current wind. We set up camp with the raft acting as a windbreak. We ate and then headed for the tent when it began to drizzle. Norm had appropriated a plastic camo rain jacket that was hanging on a bush near the raft. As darkness closed in, we heard the sound of motorboats coming down the river. One boat stopped and a young Yup'ik got out. Norm stuck his head out of the tent.

"Had we seen a raincoat? I left it here earlier today."

Norm handed it to him and without any more conversation he was back in the boat and off down the river. He was a nice, young guy with black hair and a slight slant to his eyes.

Little did we know we were about to spend forty hours in the tent.

"Rock Gardens require quick maneuvering."

--Kushkowin Wilderness Adventures Kisaralik River Description

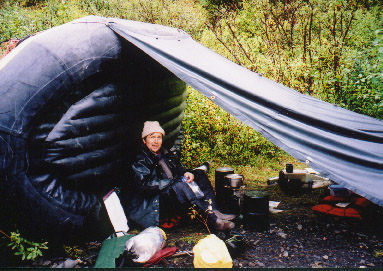

A brief moment out of the tent. Hip waders, rain pants, PVC raincoat, fleece jacket, knit hat and I still feel wet and cold! The round black cylinders are our bear resistant food containers.

Upper Falls from the air, looking upstream. That's not Lake Kisaralik in upper right, just one of many ponds.